The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Mao Zedong knew early in their campaign that to gain political control over China they needed more than sheer military might. Long before the KMT fled the country Mao Zedong was working to win the hearts and minds of the Chinese population. In fact many propaganda, or the propagation of information, tactics were already in use by the CCP prior to the civil war that consumed the country between 1946 and 1949. By its very nature “propaganda is a mass phenomenon” that must be spread to the maximum number of recipients to bring them together into a cohesive group by shaping attitudes, ideology, and perceptions (Auerbach 2014, 2). This process itself is not positive or negative, but outcomes and future repercussions for the different aspects of society and cultural beliefs can vary greatly. In this report consequences suffered by both the citizens of China and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will be explored, but the majority of space will be dedicated to the how and why of propaganda usage in the People’s Republic of China.

Mao Zedong wrote that “literature and art fit well into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part… They operate as powerful weapons for uniting and educating the people and for attacking and destroying the enemy (Powell 2007, 777).” Mao Zedong and CCP propaganda was used in conjunction with ancient rituals and beliefs, in schools and employment centers, and was even present in people’s homes and family lives. “Historical, national, and cultural contexts” become important in the use of propaganda (Auerbach 2014, 5). This means that propaganda that had fundamental success in one country or region may not prove to be useful somewhere else. The CCP and Mao Zedong must have been aware of this fact because they found ways to incorporate the values and ideals in a myriad of different situations. Communist propaganda became an aspect of daily life in China, and it became dangerous to question the wisdom portrayed on the many different posters, in popular music, or in socially constructed memories. This fear of the CCP was created over several years in the 1950s when Mao Zedong had enacted “The Hundred Flowers Movement,” “Anti-rightist Movement,” and several other initiatives that ended with violent retaliation toward many millions of Chinese citizens (Li 2014, 38). Here we will trace some of the uses of propaganda in China by the CCP, the intended and expected effects of propaganda saturation, and the unintended consequences of propaganda on the cultural aspects of society.

Figure 1- Suppress the Counter-Revolutionaries

At the end of the Long March in 1937 art was already being used to reach out to and shape the beliefs of the illiterate peasantry in Yan’an (Landsberger 1996, 197). This art was used in conjunction with other mass media information dissemination programs, but the visual component helped them to reach every member of the Chinese citizenry. Nianhua, New Year prints, were quite popular in China during the 1930s, and the CCP used this popularity to enhance their standing in society (Landsberger 1996, 198). By putting images of CCP leaders, especially Mao Zedong, communist mottos, and model and archetype citizens and military personnel on these prints they began to change the beliefs, values, and norms of the populace. In an attempt to increase the importance of these prints within society the CCP would award them as prizes, so their value was greatly enhanced and recipients were conferred a status by owning them (Landsberger 1996, 198). This moral incentive ensured that people were proud to own and display the CCP and Mao Zedong’s posters, and people were more likely to take notice of the slogans and iconography. This is just one example of propaganda used by the CCP and Mao Zedong because they were intent on establishing their rights as rulers in China.

In the 1940 essay “On New Democracy” Mao Zedong traces the revolution back to 1911, instead of 1921 when the CCP was formed (Hung, The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China 2008, 282). This allows for martyrs from past battles to be used in support of the CCP and stands as a basis for claims that the CCP were legitimate heirs to the revolution started by Sun Yatsen (Hung, The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China 2008, 282). Christian missionaries regularly placed religious holidays at the same time as holy days for Pagan religions in an attempt to use the significance associated with those times to play on people’s emotions and try to convince people to convert. The CCP did something very similar in 1949 when they officially changed the Qingming Festival (grave-sweeping day) to the Martyrs Memorial Day and required festivals to be held in local areas (Hung, The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China 2008, 283). American citizens have been influenced by the same type of propaganda since the Revolutionary War with Britain. All American students are taught about Memorial Day and President’s Day, and this is very similar to what the CCP was attempting to accomplish in 1949. By teaching future generations to respect and honor the founding members of a system it gives the current system legitimacy as a governmental entity.

Figure 2- Lei Fang, Red Martyr

Officials also used these festivities to enforce what the ideal citizen should embody in thought and actions. Chang-tai Hung makes a point to discuss memory as a socially constructed and malleable object (Hung, The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China 2008, 284). The way public memories are formed is a combination of this social construction and the influence of propaganda. This leads to how people can be controlled and how the way they think, act and see the world is manipulated. Governmental use of propaganda cannot control everything a person thinks, hears, or sees, but it does not have to for it to be an effective tool to change the minds of the populace. Even simple posters can have a huge impact on a population.

The topic of the CCP’s posters was chosen to display “the embodiment and exemplification of the value system supported by the government-maintained ideology (Landsberger 1996, 206).” This means that the CCP’s focus was on class struggle as the basis for society and the nature of the legal system (Li 2014, 36). The reason for this is simply the legitimization of the CCP’s power base and right to rule. If the CCP could convince everyone that they were acting in the best interest of the populace they would be less likely to face a rebellion or uprising. Mao Zedong had gained much popularity and fame as a military leader during the Long March and the bloody civil war with the Koumintang (KMT), so the CCP used his popularity to make him the poster child for the new People’s Republic of China. Mao Zedong’s face was painted on massive billboards in urban centers and on house walls in rural neighborhoods as the unifying symbol of the revolution, but he soon became the very embodiment of the CCP and its values (Landsberger 1996, 196). This is one of the unintended consequences for the CCP, as the importance of the party as a whole and the thoughts of other founding members were quickly forgotten by the Chinese people.

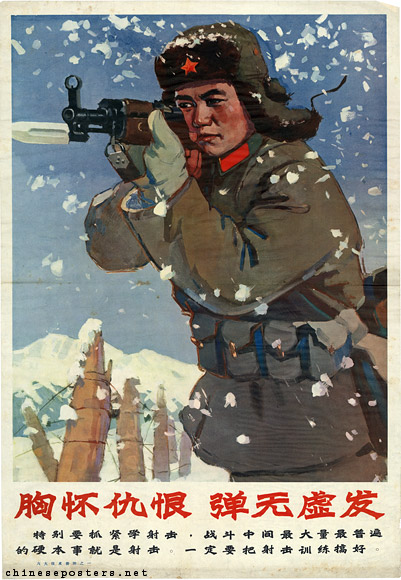

Figure 3- With Hatred in Your Heart, Bullets Won’t Miss.

The use of soldier and peasant archetypes was not a simple matter in Chinese propaganda. The Chinese Communist Party basically intended to promote loyalty from these two groups, but they needed to enforce an ideal of social obedience. The massive number of individuals and the importance of their support convinced the CCP and Mao Zedong that a propaganda program “on an unprecedented scale” was needed (Hung, The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China 2008, 281). During the early days of the civil war the idea that commemoration could be used a powerful political tool took hold, and the usage of remembrance rituals became very popular. Bereaved families called for lost loved ones to be honored, and the CCP exploited this opportunity to combine the death of soldiers with patriotism and nationalism. This political move allowed the CCP “to divert attention from the destruction of war; to legitimize armed conflict as a means of fighting enemies; to comfort the bereaved and help them to cope with personal loss; to help heal collective psyche wounds; and to educate future generations (Hung, The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China 2008, 282).” Posters and public respect of martyrdom were just the beginning of the indoctrination of individuals in the People’s Republic of China.

Lin Biao, the Minister of Defense, replaced training for the People’s Liberation Army with the study of Mao’s thoughts in October of 1960 (Li 2014, 45). This action was met with skepticism and resistance at first, but when Mao Zedong questioned the loyalty of anyone that spoke out the resistance quickly faded and the army continued to be trained in Maoist principals and to find pride in their “guerilla warfare” roots (Li 2014, 45). In 1964 Mao’s Little Red Book, filled with quotes and ideas from Chairman Mao Zedong, was compiled and printed by Lin Biao (Landsberger 1996, 2002). The soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army were required to study Mao Thought, the history of the revolution, and Marxist beliefs of a class based struggle. This essentially programmed the People’s Liberation Army to blindly follow Mao Zedong.

Figure 4- Soldier studies Mao Thought.

Mao Zedong advocated the Socialist Education Movement (SEM) in 1962 (Landsberger 1996, 201). His goal was to decide party doctrine and silence any dissenters by taking their political power (Powell 2007, 781). Mao Zedong thought that peasants would turn to capitalism if they were not indoctrinated in the thoughts and ideals of communism, and he feared loss of his power and the perceived threat posed by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. He had Maoist thought taught in schools, books printed to teach children the importance of his role in the revolution, and programs to reinforce the idea of a communist utopia. Liu Shaoqi, president of People’s Republic of China in 1962, attempted to block the initiatives put forth by Mao Zedong, and this only led to further distrust between the two most powerful men in China (Landsberger 1996, 201). This intensified Mao Zedong’s use of propaganda to astonishing levels even in the history of the CCP.

Figure 5- Mao’s picture was expected to be hung in everyone’s home.

While attempting to assert his power in the CCP Mao inadvertently turned himself into a divine figure in China. In 1962 Mao Zedong created a propaganda organization, named the Cultural Revolution Small Group in 1966, more powerful than the CCP’s propaganda department and put his wife, Jiang Qing, in charge (Powell 2007, 784). Lin Biao had instructed the People’s Liberation party “to produce art that would contribute to the construction of Mao’s god-like image (Landsberger 1996, 201).” People were encouraged to repeat slogans like, “Mao is the reddest sun in our hearts (Powell 2007, 790)” and wear pins or amulets bearing his image. These trinkets were used to “combine aspects of Mao’s persona with earlier elements of folk culture and religion (Landsberger 1996, 211).” By enforcing the idea that these amulets could protect the wearer Mao was guaranteeing that he would be associated with divine or mystical aspects of the Chinese culture in the peasants’ minds. Whether this was a connection he had hoped to foster intentionally or was simply a byproduct of the types of propaganda used may never be known.

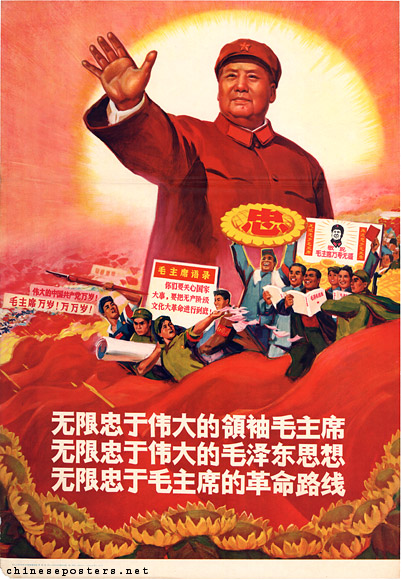

The symbolic meaning inherent in the propaganda art also helped to legitimize the CCP’s political power in China, so little was done to stop this onslaught of propaganda messages. Mao Zedong was portrayed as a leader of the Revolution, and was given the four titles of the Great Teacher, the Great Leader, the Great Helmsman, and Supreme commander (Landsberger 1996, 206). Artists were told Mao Zedong’s appearance was required to be hong, guang, liang (red, bright, and shining) and the use of grey or black could be interpreted as counterrevolutionary and punished by imprisonment or re-education in the countryside, and after the end of the Cultural Revolution many artists complained that their eyes were ruined by the heavy use of red (Landsberger 1996, 206).

Figure 6- Posters proclaimed that China should be loyal to Mao.

If this was not enough to portray Mao Zedong’s importance and divine essence to the public they were also required to treat his portraits in a ritualistic way. When hung on a wall nothing could sit higher than Mao’s picture and the frame must be perfect and unblemished at all times (Landsberger 1996, 207). These conditions hark back to some of the classic rituals around royalty and the implied connection to heaven. This is just one example of how Mao Zedong and the CCP used the long cultural memory of the Chinese people to impose their beliefs and legitimize their seizure of power.

Mao attempted, and succeeded, in infiltrating every aspect of life in China. Social organizations, religious rituals, public spaces, daily practices, and private places were focused on Mao Zedong Thought. During the Cultural Revolution citizens were expected to place Mao’s portrait in the center of each family’s alter and worship this instead of the ancestor tablets that had been the center of family ritual for hundreds of years (Landsberger 1996, 208). Mao Zedong even ordered sculptures of himself to be prominently displayed in both Buddhist temples and Protestant places of worship equating himself to a divine being worthy of worship (Landsberger 1996, 208). If these were not severe enough ways to indoctrinate the Chinese population into worshipping Mao, the CCP and the personality cult of Mao had another specific ritual that they expected people to do daily. Stefan Landsberger explains this one ritual as several steps throughout the day, and people were expected to ask Mao for instructions in the morning, thank Mao for his kindness at noon, and end the night by reading passages out of the Little Red Book in front of Mao’s picture at night and before every meal they had to say “Long live Chairman Mao and Chinese Communist Party (Landsberger 1996, 208).”

Mao Zedong’s flooding of society with different forms of propaganda was far from haphazard or simply incidental. Mao said, “… it is only through repeated education by positive and negative examples and through comparisons and contrasts that revolutionary parties and revolutionary people can temper themselves, become mature and make sure of victory (Landsberger 1996, 203).” There was hardly an area that was not controlled in some part by Mao Zedong or those that supported his ideology in the communist party. Even public performances were regulated during the Cultural Revolution. Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong’s wife, allowed only five operas and two ballets to be presented during the Cultural Revolution (Landsberger 1996, 204). Jiang Qing and Mao believed that by controlling what types of stories the masses watch and how they are supposed to see the hero of the story that people would internalize the ideology of the communist party. It would seem probable that if the population of China internalized the ideology of the party then they should support Mao Zedong as the father of the country too.

Figure 7- The White Haired Girl- One of the two ballets allowed during the Cultural Revolution.

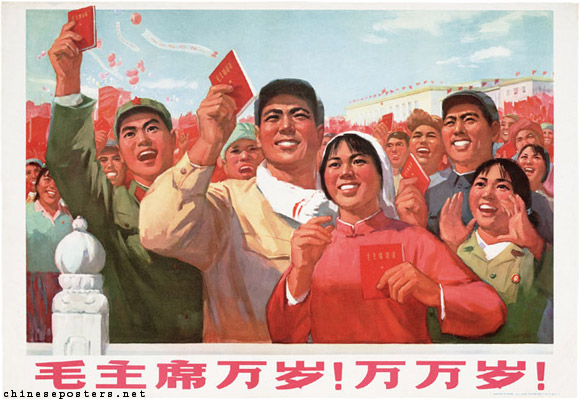

The combination of all of these forms of propaganda, Mao Zedong’s speeches, and military might of the People’s Liberation Army set China up for one of the most chaotic times in the recent memory of the world. Propaganda was extremely effective and prevalent in the daily lives of people. Children that had been indoctrinated in each social system were becoming adults in the 1960s and 1970s, and they viewed Mao Zedong as a god. This forced the CCP to simply follow his directives because if they publicly denounced his ideology then they would be denying the legitimacy of their right to rule China. The social mentality of the population was extremely violent since they had been raised to believe the model citizens were military and martyrs that would turn against anyone that was considered an antirevolutionary. The CCP never expected to give Mao Zedong as much power as he had during the Cultural Revolution, early reports indicate that Mao was only supposed to appear in conjunction with other party leaders, but public persuasion and social memory turned him into an all-powerful, all-knowing dictator that would kill, imprison, or send for re-education anyone that even questioned his methods or ideology. This shows how propaganda can become far more powerful than originally intended and push the wrong people into positions of power.

Figure 8- The cult of Mao became a social movement.

Figure 9- Even women were taught that it was right to fight and die for Chairman Mao.

Bibliography

Auerbach, Jonathan and Russ Castronovo. The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Hung, Chang-tai. “The Cult of the Red Martyr: Politics of Commemoration in China.” Journal of Contemporary History, 2008: 279-304.

Hung, Chang-tai. “The Red Line: Creating a museum of the Chinese revolution.” The China Quarterly, 2005: 914-933.

Landsberger, Stefan R. “Mao as the Kitchen God: Religious aspects of the Mao cult during the Cultural Revolution.” China Information, 1996: 196-211.

Li, Xiaobing and Xiansheng Tian. Evolution of Power: China’s struggle, survival, and success. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2014.

Powell, Patricia and Joseph Wong. “Propaganda Posters from the Chinese Cultural Revolution.” The Historian, 2007: 777-793.

Wang, Qian. “Red Songs and the Main Melody: cultural nationalism and political propaganda in Chinese popular music.” Perfect Beat, 2012: 127-145.

All posters are from Chineseposters.net.